You are here

1986 Examiner Report

It was 10 years ago this week.

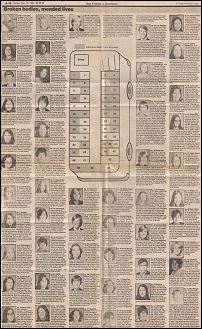

Fifty of the best and brightest children from Yuba City, a farm and orchard community alongside the Feather River in Sutter County, climbed aboard a big yellow bus that warm spring morning.

Most were honor-roll students and a few were genuinely gifted, genius-level youngsters. Several were leaders of church youth groups; many who were not had recently been converted by their fellow choir members to religious beliefs that surprised even their parents. All of them loved music and some had mastered as many as five instruments.

Within about 90 minutes, 28 of them were dead or dying, along with a beloved music teacher. Another 22 had injuries that required hospital care.

Most of these survivors have physical scars they will bear for the rest of their lives. All were permanently changed. They lived through a horror no one but their seatmates could fully comprehend.

The accident "tore the heart out of this community," one Yuba City resident said at the time.

"I think it touched everybody," said Dorothy Matson, whose 15-year-old daughter, Joanne, died in the crash. There were only 15,000 residents and "if they didn't know a child, they knew a sister or a brother or the parents. They knew somebody that knew that child."

Jackie Bowen remembers driving into town at the time of a memorial service at the high school football field, a week after the accident. Ten thousand people were at the service.

"There was not a person on the streets. All the flags were at half-mast. It was just like a ghost town. That's when it hit me. This really happened. This is not a nightmare."

It was, perhaps, the most difficult moment in the history of what has seemed a luckless town. It was worse than the 1971 discovery that Juan Corona, a local farm-labor contractor, had killed 25 transient workers and left them buried in the orchards around town. No one knew those victims.

It was worse than the floor of Christmas Eve 1955, when the Feather River broke through the levee just before midnight and drowned 36 people, catching them in their beds as they slept and their cars as they tried to flee. The bus crash hit the town harder, because the victims were so young.

The effects of the crash are still there, just under the surface. They can be seen inside the two-story cul-de-sac of choir.

Christina Estabrook has an edgy feeling. Most of her good friends from high school are dead or have moved away, "and I've come back and lived in the old hometown. I feel like I'm a loner out here, the survivor who's left behind or chose to go back."

Christina Estabrook has an edgy feeling. Most of her good friends from high school are dead or have moved away, "and I've come back and lived in the old hometown. I feel like I'm a loner out here, the survivor who's left behind or chose to go back."

She also senses herself living in the shadow of the former wife, Cristina Estabrook, whose photograph she pulls out to be included in the conversation.

"I've always felt that I've been no competition, not even in the same ballpark. I've elevated her to a goddess-like position and felt that their first marriage was perfect. I feel like I'm kind of the runner-up, but will do what I can to make him happy and just hope I can be a good wife to him."

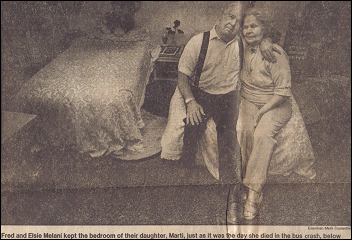

The effects are also in the homes where, in the darkness of their bedrooms, mothers and fathers still cry; where the room of a long-dead child remains unchanged, with fading pompons gracing the walls; where the approach of Halloween or Christmas still brings an impulse to take a pumpkin or small Christmas tree out to Sutter Cemetary; where thoughts turn occasionally to those who were harder hit, where the tragedy contributed to divorce or to fatal illness; where the thought of the school district, or of a certain local bus company, can bring up a hateful bile.

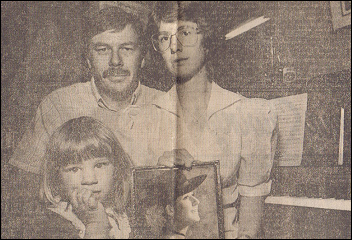

Above: Fred and Elise Melani kep the bedroom of their daughter, Marti, just as it was the day she died in the bus crash.

The voice of William Karperos, superintendent then and now of the Yuba City Unified School District, is tense as he declines to talk about the tragedy.

"It's been 10 years," he says, "and the terrible tragedy has faded, but not completely. I can see no good reason to have a 10-year report, from the school district's point of view."

The district, in whose charge the choir left on a 25-year-old, poorly maintained bus, driven by a man unfamiliar with its emergency braking system, was a defendant in numerous lawsuits, all of which were settled without any admission of liability.

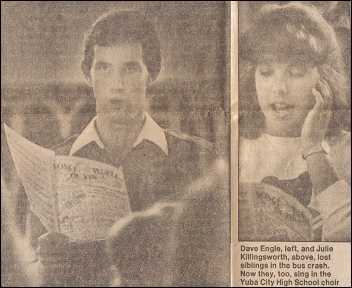

In all the town's schools, music education thrives despite the decimation of such programs in almost every school in the state after passage of Proposition 13, the 1978 property-tax-reform initiative.

The choir bus accident makes it politically imprudent for the school board to cut the music program, says Jane Roberts, a substitute music teacher, concertmaster of the community symphony and mother of a student who survived.

In the district bus yard, a transportation supervisor is now responsible for the safety of every student who travels under school auspices. This man, Phil Gardiner, must approve the mode of transportation on every field trip; he will personally inspect the charter bus and the qualifications of its driver if district transportation is not being used; he has taken district drivers to San Francisco for on-the-road training before allowing them to haul students on those unfamiliar streets.

At the high school, where a sign 10 years ago proclaimed, "We Will Remember," a memorial courtyard now is vandalized and littered. Students use instruments purchased with donations in the dead choir members' names. Scholarships are given annually in their memory.

In the general population - half of the people in Yuba City today didn't even live there a decade ago - strong feelings still lie just below the surface.

"Ten years, I didn't think anyone would remember May 21," restaurant hostess Carol Babler says. Now 22, Babler was in junior high at the time, but knew many of those on the bus because they had helped Cristina Estabrook stage the musical "Bye Bye Birdie" at her school that spring. She taught her Spanish and music. After the accident, Babler's parents were so concerned with her reaction that they sent her to a counselor.

"I had never known anyone to die before. My parents didn't know what to do with me."

There isn't a parent whose child was on that bus who doesn't remember where he or she was, what was happening, when first word of an accident reached Yuba City. The radio and television broadcasts reported many deaths. But there was no way of finding out by telephone if your child was dead or alive. Most parents had to drive to Martinez to find out.

Alfonso and Amanda Ortega set out with a certain confidence that their son Bobby would be a survivor. In fact, with all the CPR classes he had taken, they thought, he was probably helping with the rescue.

Then they came to the crash site, and Alfonso stopped the car.

"I jumped out of the car," Amanda remembers. "The bus was upside down. Squashed."

"There were no kids there," Alfonso says. "I got very scared," she recalls. Their son was dead.

Chester Matson, 77, remembers passing the bus that day, too, as he and his wife drove to the Contra Costa Emergency Services Office.

"I saw the bus lying on its top and I told Dorothy, "You might as well make up your mind that we've lost a daughter."

Another sight from that day sticks in his mind, as well.

"When we drove into town we saw this long line of people going into a building. We wondered what that was. We found out later it was the people of that town lined up to give blood for the children."

The arriving parents, consumed by worry, were directed to the Contra Costa County Sheriff's Recreation Hall.

"When we got there, as soon as I got out of the care, I knew what they were going to tell us," says Alice Rooney, whose son Larry died.

"You could just feel something in the air, I mean it was thick. You could feel it. And we walked in and they had ministers and priests and people were screaming and crying."

County disaster officials had done all they could to ease the blow. There were clergy of all faiths for counseling, doctors and nurses for those parents needing medical care, and just plain people, caring people, ready to surround and give support to the grief stricken.

Still, it was difficult. From the moment the parents arrived at the front door, the brutal division was made. Those who had to be told they had outlived their children were sent to a room in the back.

The Engstroms and the Youngs had been close friends for years, brought together by their daughters Pamela, 18, and Christina, 17. The girls had played together since primary school. Christina was invited along on camping trips with the Engstroms. When the Youngs went to their cabin on the American River, Pamela was invited. The day before had been Pamela's 18th birthday. The surprise party, attended by the Engstroms and many kids from the choir, had been in the Young's backyard.

The two sets of parents - Charles and Vernie Engstrom, Dick and Joan Young - arrived at the building almost simultaneously.

"I told them our names and they said, 'Oh yes, your daughter is in Veterans Hospital,'" recalls Joan Young. "And I saw our friends the Engstroms go into that back room."

Vernie Engstrom recalls, "Someone at the door asked who we were, then kept asking other questions like what's your religion. It was really starting to annoy me and I said, 'I want to know what's happened to my daughter,' and she said, 'OK, follow that lady.'"

"Well, that lady turned out to be a woman deputy sheriff. She got to a little room and she told us, 'I don't know how to tell you Pam is dead and you're the 15th family I've had to tell this to.'"

"She was just shaking."

Everyone touched by the accident carries the mark today.

Xon Burris, a firefighter, cut and crawled into the wreckage to rescue and cradle frightened and trapped 15- and 16-year-old girls until they could be pulled safety. At night, when he closes his eyes, he can still see their faces.

Xon Burris, a firefighter, cut and crawled into the wreckage to rescue and cradle frightened and trapped 15- and 16-year-old girls until they could be pulled safety. At night, when he closes his eyes, he can still see their faces.

There's one in particular - the girl with the little earrings. Her legs were trapped and she kept calling for her mother. He held her for such a long time and he doesn't know if she lived.

When the Engstroms emerged from the back room having learned of Pamela's death, they did something few grieving parents were capable of that day - they went to visit a child who had survived, Christina Young.

The Rev. Robert Adams, an Episcopal minister who was at the accident scene that day and performed last rites for the dead, went later to a hospital and saw the injured and their parents.

"I told the parents they were not going to meet their child that had left home. If that child was conscious at all, they were going to meet somebody who had been through an experience they did not know about, and that the children would be talking to them about that experience. And if they wanted to communicate with them at all, they had better listen and not try to remake the world the way it was before it all happened."

Pat Skidmore walked right past her daughter Annette when she entered the ward. Annette's face was so cut and swollen that her mother had to read the name on the bed before she could be certain. Annette had been one of the last pulled from the bus and was in emotional shock, her mind running over memories of screams and classmates struggling for breath.

She remembered lying there, her legs tangled in the twisted metal, and hearing a rescue worker say, "I think we got everybody," and screaming no, she was still alive.

She remembered being placed in an ambulance with 14-year-old Larry Shearer. "They were working on him and I was trying to ask them what was going on. They told me to be quiet. Larry died in the ambulance."

Then on the emergency-room table, when the nurses were cleaning the blood and glass from her face and hair, and, thinking she was asleep, whispering, "how awful" and "30 people dead."

Steve Eberhart thinks he was asleep when the bus went over. He woke up five days later in Highland Hospital in Oakland.

"The first sight I saw was mother leaning over the bed. The first thing I asked was, 'Is the trip canceled?' I didn't know where I was. Here's mother with tears in her eyes. She started to cry and laugh at the same time. She said, 'I guess you could say that.'"

Gary Vaught isn't sure how long he was out. His mother, Gladys, says it was 10 days and that doctors told her the first day that her son had a very critical head injury and would probably die before the night was over, "and if he didn't die, he would be a complete vegetable."

Gary Vaught isn't sure how long he was out. His mother, Gladys, says it was 10 days and that doctors told her the first day that her son had a very critical head injury and would probably die before the night was over, "and if he didn't die, he would be a complete vegetable."

"I remember some things from the coma," says Gary Vaught, who went on to finish high school with A's and B's the following year.

"It was like my mind was alive and awake but my body wasn't functioning. I remember a kind of weightlessness, like drifting out of my body. I could see myself on the bed, then I felt myself going through a tunnel."

"Next thing I knew I was in a dark room. There weren't any walls. Then I saw a light. I could see it off in the distance, but it was dim. So I started moving toward the light."

"I remember pausing at one point in this journey and wishing I was at that light. I was then instantaneously transported to that light."

"Everybody was wearing robes and singing, white robes. I spoke to this one individual. He was older. He asked me whether I'd like to return to my life, complete my life, or whether I wished to stay where I was. I told him there were several things I wished to complete in my life and I wanted to return."

"I remember waking up at that point and I was in the hospital."

Kelly McClung also remembers a choice between living and dying. Her left side was crushed - broken ribs, collapsed lung, a crushed spleen, broken left arm and broken collarbone. Doctors didn't expect her to live through the night. Her parents were told she might have a better chance in San Francisco General Hospital because they had the best trauma team in the area, but moving her would be a risk. They took the chance.

Kelly McClung also remembers a choice between living and dying. Her left side was crushed - broken ribs, collapsed lung, a crushed spleen, broken left arm and broken collarbone. Doctors didn't expect her to live through the night. Her parents were told she might have a better chance in San Francisco General Hospital because they had the best trauma team in the area, but moving her would be a risk. They took the chance.

"It was awful. I couldn't breathe. They were forcing air into me to keep me alive. I thought there was so much air - they're killing me. I remember laying in the ambulance, and all these faces staring at me and I'm telling them too much air, and they couldn't understand."

She was in intensive care for three weeks. The pain was severe.

"I remember one night I had a temperature of over 104. It was May in San Francisco and they had me in front of a window, packed in ice. At that point, I knew all I had to do was give up and that would be it. I was close to giving up. I'm Christian and I wasn't afraid at all. I thought, I'm tired. I hurt too much. Why am I doing this?"

"I had a really wonderful doctor, an intern, who stayed all night with me, talking to me and telling me if I didn't start trying I wasn't going to make it and I had to make it 'cause too many people were counting on me.

"The crisis passed and then I had the uphill climb of getting better. I graduated in the hospital. The doctors and nurses made a diploma and hat. I walked to the intensive-care refrigerator and back and they sang 'Pomp and Circumstance.'"

For those touched by the crash, this has been a decade of struggle. If you didn't struggle, say the survivors, you died, like the Rev. Robert E. Shearer. Larry, 14, was his fifth and favorite child.

"He was the perfect kid, the one you always dream about having," says Larry's mother, Beverly Pooley of Sun City West, Arizona.

He was a straight-A student, valedictorian of his eight-grade class, a year early for the choir, really, and already arranging some of its music. He started taking math at the school when he was in junior high. He loved science, especially physics, and spent hours alone working on art projects.

After Larry's death, Shearer no longer felt right living in Yuba City. The family moved to a church in Southern California within four years.

"We were there about two weeks when he started having symptoms," Pooley says. "We found out my husband was dying of cancer. He lived 15 months and passed away. He was 51."

"The doctor said it was the stress of the death - this was his favorite kid and everyone knew it. The doctor said my husband couldn't get over Larry's death, couldn't accept that God took him from us."

"Just before he died, he said he saw Larry getting on a school bus and he was all dressed in white. He said it won't be long before I see him. That was two weeks before he passed away."

"My husband is buried 20 feet from Larry. That was his last wish, to be buried next to him."

She stayed to struggle: "I really felt, now what do I do? I was still a young person. At age 44 I had suddenly become a widow. I had

married young and had never had to make a decision before." She married another man and learned to cope with the death of her son.

"I miss Larry a lot, think of him a lot. I wonder what he'd be doing. Would he have a family now? I place flowers in church in his memory every year. I have gone back and visited the grave. He was one of a kind."

And while she was recovering, she helped her other children along the same path. It was toughest on their youngest son, she said. He was 12 at the time and he couldn't talk about it until about four years after. He and Larry loved to play basketball and they had a hoop. And he'd go outside and shoot a couple of baskets, then slam the ball down and walk off. He kept everything in himself.

"Then one day he and his girlfriend had a spat and he came home and he wanted to talk. He broke down and cried that he missed his brother and his dad. He wanted his mom to love him." Sometimes, the ache of loss was eased by a sign of caring from others.

Helen Mudge remembers the girlfriends of her 16-year-old daughter filling her house for weeks after the accident, as if in an effort to fill the void.

"They were hard to figure out," she says. "They came and went as though this were home. I came home, three weeks after the accident, I had gone back to work and I came home one afternoon and a group of her friends had broken in the kitchen window and climbed through and they were in the kitchen making her favorite chocolate-chip cookies for me."

"I remember one night we were siting here and we had a whole living room full of little girls. They kept coming. Gradually it petered

out, but not for several years," says her husband, Tom Mudge.

(from the surface of Planet Genesis as they observe the Enterprise A self-destruct in the atmosphere high above them)

Kirk: "My God, Bones, what have I done?"

Dr. McCoy: "What you had to do, what you always do. Turn death into a fighting chance to live."

- Star Trek III: The Search for Spock 1984

(Larry Shearer loved Star Trek, the original television series)

(...Just so you know...)

(~ Yours Truly)

Eldrid and Bernadette Barfield remember the woman who ran up their car as they were leaving Grace Baptist Church after the funeral of their 16-year-old daughter, Bonnie.

"As we were leaving for the cemetery, some lady stuck a package through the window of the car and handed it to my wife," Eldrid

recalls.

They opened it when they got home. Inside was a poem that circulates among parents whose children have died. Some call it "God's Promise"; others call it "A Child Loaned." The message is that a child is only an instrument of God, loaned to be taught and loved:

Now will you give her all your love

Nor think your labor vain,

Nor hate me when I come to call

To take her back again?

The letter said the woman was from Rocklin, but used to live in Yuba City and had met Bonnie at Grace Baptist Church. Though her parents were not particularly religious, Bonnie had joined the church three years earlier.

"She said she knew Bonnie from the church and thought she was an exceptional person. She said that when she lost her son Paul to cancer a couple years earlier, this poem had meant more to her than anything else."

"Like this lotus blossom from the fountain

in front of the Mariposa Hotel in

Yosemite National Park,

are parents the reflection of our children...

or are children the reflection of their parents?"

- Tom Randolph

November 16, 2010

The more parents found out about the accident, the angrier they became.

According to the National Transportation Safety Board report on the accident, Highway Patrol reports and interviews with the parents, they learned:

This wasn't a district bus. None had been available and the choir had hired one from a private company, with its own money. Each kid pitched in and they scraped together $250. That was enough to get a 25-year-old Crown Coach from Herb Brown, who ran Student Transportation Lines out of his Marysville gas station. There was a newer bus available, but the students liked the roomy old No. 16, which they had ridden in on choir ski outings and singing trips. Besides, choir director Estabrook told the Highway Patrol, the late-model coach was more expensive. A complete safety inspection of old No. 16 should have revealed a frayed air-compressor belt, long overdue for replacement, that would break on the field trip and leave the bus without brakes. CHP Officer E. Meacham was in the bus company's yard four days before the accident and would have given No. 16 its annual checkup, he said in a report, but was told it would be sold or traded before the permit expired June 12, 1976. The bus company had received the CHP's lowest rating, a C, because of "inadequate maintenance records." The rating had been in effect since 1974, but only the CHP and the bus company knew this. And no one told the school district.

The National Transportation Safety Board could find no evidence the CHP had used the tools the law gave it to deal with deficient public carriers - from warning letters to criminal prosecution - against the Marysville company.

Then there was the matter of the driver. Evan Prothero, 50, was badly injured in the accident and nearly died. Most parents say today they have let go of most of their anger against the man. He needed the job and didn't know, when he got behind the wheel, that he was unprepared for the job. It came as a surprise to the parents to learn from CHP reports that the vehicle carrying their children technically was not a school bus, driven by a licensed school-bus driver. It was yellow, and it had the words "School Bus" on its body, and it and it had those blinking lights that the drivers turn on to stop traffic while children disembark. But the lights and the words had been taped over for this trip, thus legally converting it to a

charter bus. This meant that Evan Prothero, a trucker by trade and licensed in California to drive anything but a school bus, could transport the choir.

According to reports of the CHP and the federal safety board:

- Prothero had driven school buses only twice before in his career - both times in the last couple of weeks.

- He had approached Herb Brown at a funeral two weeks earlier, asking for a job. He had driven trucks for Brown's father-in-law for 25 years and was serving as a pallbearer that day for the uncle of Brown's wife.

- The only two buses Prothero had operated before were markedly different from this one. Brown checked him out on old No. 16 that morning, sitting with him as he drove it around the block, backed it up, studied the gauges and switches.

Brown would tell the CHP later that he was certain Prother knew all about the bus' brake and emergency system. The driver would tell the safety board he did not. Prothero seemed to miss all warnings that something was wrong with No. 16 that day, the safety board said.

Several students told the Highway Patrol that the bus door - which was held closed by air pressure - started blowing open on the trip. This reflected a loss of air pressure and thus a possible danger of air-brake failure.

Dean Estabrook, following the bus down Interstate 80 near Fairfield, noticed a strip of something flapping against the road beneath it. He thought it might be a static-guard strap. Instead, he was told later, it was probably the broken air-compressor belt.

The clearest indications of danger, though, were on the dashboard. Right before the driver's eyes were a warning light to indicate dangerously low air pressure, and a separate air-pressure gauge. Both were working, according to the CHP.

When the federal safety board held its hearings that August in the Yuba City High School gymnasium, there was testimony before the board that the driver knew something was wrong with the bus, but thought it was low on oil, that this boss had told him the old bus burned it up. When he saw the strap flapping beneath the bus, Estabrook also noticed some steam or smoke. He flagged the driver down, into the Vista Point area overlooking the Benicia Bridge. The bus used its last available air pressure at this stop.

Estabrook mentioned the smoke, but forgot to say anything about the flapping strap. Students told the Highway Patrol that the driver pointed to a red light on the dash and said he was low on oil. Estabrook said he had been in the area before and knew the location of a gas station.

Prothero hadn't been pointing to the oil-pressure warning light, though, according to witnesses. He had pointed to the air-pressure warning indicator, which was located beside the oil-pressure gauge. His brakes were gone. Prothero testified the bus was low on oil and that he pointed to the oil-pressure indicator.

The two vehicles pulled out and onto the Benicia Bridge. Students dozed or read or sang or looked a the mothball fleet below.

Estabrook took the first exit after the bridge, the Marina Vista ramp. As he followed him, Prothero might have noticed a small yellow sign advising a 20-mph speed. At one point, though, it is partially blocked by a light pole. The sign also tends to blend with the background of golden-brown grass on the nearby hills.

The safety board calculated the speed of the bus when it hit the off-ramp wall at 45 mph. If Prothero had seen and reacted to the sign as he entered the exit lane, he might have touched the brakes and discovered he had none. There was still time to ease back on the highway and coast to safety.

Even having taken the off-ramp and found his bus with no brakes, the driver had one last chance to avert the disaster. The bus had a fully operable emergency-braking system with a supply of air pressure adequate to halt the vehicle. All Prothero had to do was flip a switch on the steering column and hit the brakes again. The driver said he didn't know where the switch was. It had been on the dashboard of the other buses he had driven.

"You will make my strength your own.

"You will make my strength your own.

You will travel far...but we will never leave you.

You will see my life through your eyes as

my life will be see through yours.

The son becomes the father and the father, the son...

you will be different, sometimes you'll feel like an

outcast, but you'll never be alone."

~ Jor-el to his son Kal-el and Kal-el to his son Jason

Superman Returns Hogarth: "You are who you choose to be. (cringing) Choose!"

Giant: (closing his eyes) "Superman!"

The Iron Giant, 1999

If you're wondering what I'm doing,

I'm breaking into your spiritual house

through your spiritual window

and then into your spiritual kitchen

to make your favorite spiritual cookies.

If you don't like it, you can go to your

spiritual bedroom and not come out for

a spiritual month.

(~ Yours Truly!)

Some parents sued, thinking this was the way to punish the responsible.

Some, like Vernie Engstrom, felt a lawsuit would accomplish nothing and the loss of a child could never be compensated. She and others put their energy into seeking school-bus safety legislation and making sure the federal safety board's recommendations were acted upon.

No one is fully satisfied.

Some legislation was passed because of the tragedy. Today, only experienced bus drivers, with 15 hours of classroom training and 20 hours of on-the-road training, can legally drive students on school activities. However, a recent bill that would have required all California school buses to meet federal standards or carry signs saying they don't was vetoed by Gov. Deukmejian.

Vernie Engstrom wrote him a sharp letter, saying, "Only someone who sent a child off in a school bus on a school trip and had her returned in a casket can understand my depth of feeling regarding school-bus safety."

The governor never responded. But he did include $100 million for school-bus safety in his next budget.

"I'm not going to make any great impact but I'm going to be nicking away at it, because you can't let your kid die and not do anything about it. You know?" Engstrom says. Her biggest disappointment came when Caltrans refused to implement the federal safety board's top-priority recommendation for non-legislative changes in the wake of the accident.

The board called for a new, large exit sign at the Marina Vista ramp, including a diagram of the curve along with the speed warning.

Caltrans has a district office in Marysville and is a major employer in the Yuba City area. Six of the children on the bus that day were from Caltrans families, according to spokesman Bob Halligan. Yet the agency still refuses to change the Marina Vista sign. There haven't been enough accidents there to warrant such an oversized sign, Halligan says.

Every other government agency, including the CHP, made the changes recommended by the safety board, Engstrom says. "Only the Department of Transportation took the stance that they were perfect."

Those who sued in hopes of fixing blame and punishing those at fault found cash, but little satisfaction, in Contra Costa County Superior

Court.

Judge Coleman Fannin pushed for a settlement, saying the families of the dead children and the survivors should save themselves the trauma of reliving the accident. Besides, he said, the bus company was insured only for $1 million. If they couldn't prove liability on the part of the district or state or bus manufacturer, the families might end up with very little.

Only one set of parents actually got their day in court - Fred and Elsie Melani, parents of Marti Melani, killed at age 18. She was like an only child, "a change-of-life child," born to Elsie when she was 45 years old. They had a son, already grown when Marti was born, who avoided a similar accident in 1957, when strep throat kept him from joining his Cal Poly-San Luis Obispo football teammates on a flight to a game. The plane crashed, killing 19.

The Melanis had been offered $75,000 to settle. They insisted on a trial and Fannin had the jury consider the amount of damages before it considered fault. When the jury awarded $150,000, the defendants agreed to split the costs rather than go through a trial to fix blame.

Of the others who sued charging wrongful death, most got $75,000, a figure Fannin says is low by today's standards for the death of a child.

Bernard and JoAnn Engle were paid $225,000 for the loss of their twin daughters, Carlene and Sharlene.

Dean Estabrook was paid $200,000 for the loss of his wife, Cristina. "The fact that she was a breadwinner was a factor," Fannin said.

Those who did not sue charging wrongful death were asked by the insurance companies to waive all future right to sue in exchange for $25,000.

Those who lived through the crash were awarded amounts ranging from $10,000 to $400,000.

Many of those who got money expressed feelings of guilt or further grief at the idea of profiting at the loss of a loved one. "To me, the whole process was odious," says Dean Estabrook.

The Ortegas took the money to the bank and never touched it. "We call it Bob's money," Amanda says. "We already had all we needed."

"All I wanted was my kid," Alfonso says.

Tom Mudge had wanted to go to trial and force a public revelation of wrongdoing, but accepted the settlement believing he had achieved some of what he set out to accomplish.

"I said, 'Well, now we can get the transcript of all these settlement discussions so that I can find out where the liability lies.' My concern about liability was about how much responsibility the Yuba City school district had for all of this."

The district had said all along that it had none, because it was a charter bus. Mudge's lawyer told him the judge had "sealed in perpetuity" all records of the settlement discussion.

Phil Illerich, a school-board member since before the accident, said he never knew if the district's insurance company paid anything. He's always been curious, he says.

Two of the plaintiff's lawyers, James Boccardo of San Jose and Phil Cook of Yuba City, said every defendant, including the school district and the state, paid something.

Fannin says, nonetheless, that negligence and liability were never proved. The parties settled. Mudge is still bitter, and thinks the public agencies that shared responsibility for the deaths of the children escaped critical review because the world's attention shifted so quickly from Yuba City.

In July 1976, for instance, three young men kidnapped a school-bus load of children from Chowchilla and buried them in a moving van, planning to demand a ransom. Months later they said the idea for the crime, in which the children escaped, came to them from the Yuba City tragedy. By year's end, the Yuba City crash, which drew worldwide attention in May, ranked only third on the Associated Press list of major California stories in 1976. The Chowchilla story was first. The Patricia Hearst trial was second.

"Remember when that tragedy happened in Japan, when that big airliner crashed and all those people were killed but one? The president of the airline immediately resigned. I don't know if they accept the resignation but they open it up," says Mudge.

"Here, everyone runs for cover. Hunker down until the dust settles. Personal and institutional interests are greater than the safety of the kids. Don't say anything. It'll go away. And it's true. That's exactly what happened for the school, for Caltrans with that miserable sign, for the Highway Patrol. Nobody asks the heavy questions after 10 years."

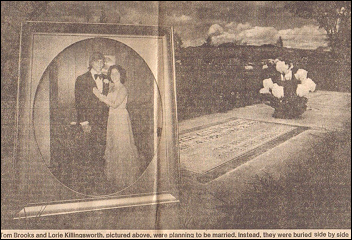

For Lee Killingsworth, one of the most helpful steps in coming to grips with the loss of her daughter Lorie was one she took to help one of the surviving children. Kelly McClung, a friend of Lorie's, had been through so much, coming back from injuries that nearly killed her, losing her beautiful voice because of the tubes doctors had to run down into her lungs, overcome the fear that if she allowed herself to become close to the man who

For Lee Killingsworth, one of the most helpful steps in coming to grips with the loss of her daughter Lorie was one she took to help one of the surviving children. Kelly McClung, a friend of Lorie's, had been through so much, coming back from injuries that nearly killed her, losing her beautiful voice because of the tubes doctors had to run down into her lungs, overcome the fear that if she allowed herself to become close to the man who

would one day be her husband, he would die just like her friends on the bus.

Lee Killingsworth and her husband, Max, a Marysville school principle, were talking with Kelly one day about her fear of buses. Max asked if she'd like to try to get on a school bus and just sit.

"So I took her out there," says Lee Killingsworth. "And she and I got on the bus. And the bus driver was on there, but nobody else. Kelly and I walked hand in hand on the bus. She took me back. I must have been right by the emergency door. We sat in the seat and she said,

'Lorie and Tom were right in front of me.'"

Tom was Lorie's boyfriend. They expected to marry. Their parents had them buried side by side.

"We sat there a long time and talked about it, and cried. And then I got off the bus and my husband asked her if she would like to go for a ride. So they just took her around the block in the back of the school."

"We sat there a long time and talked about it, and cried. And then I got off the bus and my husband asked her if she would like to go for a ride. So they just took her around the block in the back of the school."

"She was so glad that she had done it. It helped her, I hope. It helped me."

Kelly McClung is Kelly Balfour now. She married the man who, as a high school boy, got to know her by visiting in the hospital. She is a professional dancer, using a talent she discovered when she found she had lost her singing voice and turned to ballet as therapy.

Some days, she thinks the accident may have really been a blessing for her.

"I couldn't imagine my life without it," she says. "Sometimes I think about that little girl in the hospital, with the tubes in her, and I cry. And I have a lot of scars on my body so, that I have to be clever with clothes. Sure, I'd like to have a nice pretty stomach like every other girl. But that's so trivial, really."

"One thing it taught me that's neat is that I'm a survivor. You can cut my arms off and I'll learn to eat with my feet. You cut my feet off and I'll take up wheelchair basketball. You can't keep me down 'cause I've been through a lot. I think most of us feel that way."

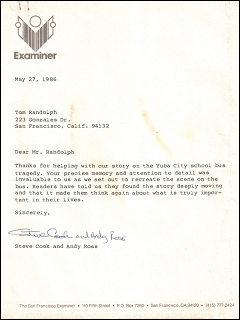

This report was prepared by

Examiner reporters Stephen Cook and Andrew Ross. The accounts of the event surrounding the tragedy are based on information compiled from police reports, findings by the National Transportation Safety Board and interviews with more than 80 people. Among those participants were members of 46 of the 50 families directly affected by the accident, as well as lawyers, judges, clergy, police, firefighters, medical personnel and state highway officials - all of whom were touched by the tragedy of May 21, 1976.

Here she is in all her glory & splendor... as she should have been, as she should be - a 1950 Crown Coach ready to drive the road and get her charges to their destination safely and securely.

If a call could have gone out on May 21, 1976 for this once luxurious coach, it might have said "Yellow Lady Down." She gasped her last breath for us...and from her long youth she was rendered by gravity into a mean carcass.

Like so many of us, she deserved better.

Like all of us, she wanted better for all of us.

More than 24 years after this article was published, I present it to you. After more than 24 years, I have read it again...over and over...in order to share it with you. I have had many thoughts and many ideas of what I'd like to say now. But of all of them, I would only like to say this:

More than 24 years after this article was published, I present it to you. After more than 24 years, I have read it again...over and over...in order to share it with you. I have had many thoughts and many ideas of what I'd like to say now. But of all of them, I would only like to say this:

"Whisper to me of your remorse...

and I will exchange your tears

with uncommon gladness."

~ Tom Randolph

November 18, 2010

Anniversary 1986 | 1986 Examiner Report | The Bus Diagram